Trading through the pandemic: recent trends in UK exports and imports

Key points

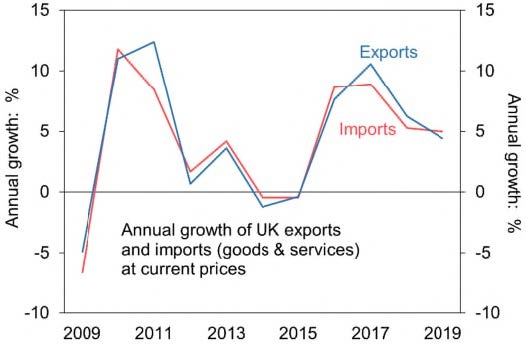

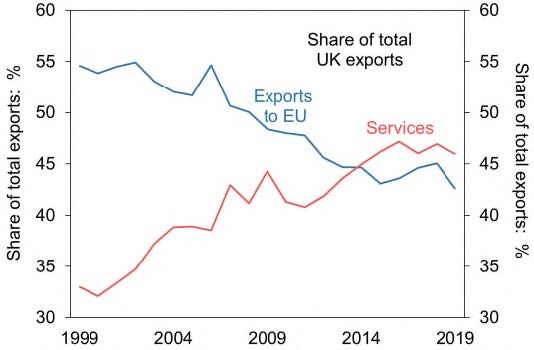

- The UK’s exports have expanded at a brisk pace in the past few years, helped by solid global growth and the depreciation of sterling in the wake of the EU referendum. At the same time, the long-standing shift from goods to services has stalled, while there are signs that Brexit has already had an impact on trade with the EU.

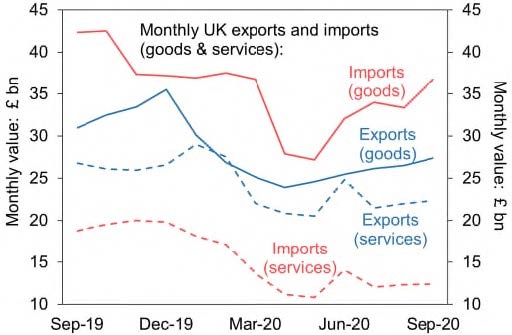

- After steep falls earlier in the year, as the Coronavirus pandemic struck, trade flows have revived in the pastfew months. Indeed, the value of goods being imported into the UK is now back to normal levels. But goods exports are still markedly lower, and trade in services will not recover fully until people are able to travel again.

- Imports will continue to expand in the coming months, in response to brisk demand for consumer goods, pre-Brexit stockpiling, and purchases by the government of personal protective equipment (PPE) to facilitate the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines. Looking further ahead, however, some important trade flows will be dampened as a result of the UK’s final extrication from the EU.

The four years since 2015 have been pretty decent ones for British exporters. The UK’s export earnings haven’t grown so briskly since before the global recession of 2008-09. But the Covid pandemic has upset the apple cart, with trade flows falling off a cliff earlier this year. Although a revival is now under way, the recovery is far from complete, and the ‘new normal’ is unlikely to be exactly like the ‘pre-Covid normal’, not least because of Brexit. Even before the UK’s formal departure from the EU at the end of January 2020, its impact was already being seen in the trade statistics. There will inevitably be more to come, with the new trading arrangements imposing extra costs, and in the near-term the negative impact on UK-EU trade is unlikely to be made good by new agreements

that might be struck with other countries. The upshot is that exporters are likely to find the going rather tougher in the years ahead.

The pre-Covid normal

Let’s begin with a few basics. In 2019, the value of all goods and services exported from the UK amounted to £691 billion, while imports were valued at £721 billion, giving a total of just over £1.4 trillion. With imports exceeding exports, there was a deficit of £31 billion, which was equivalent to about 1.5% of GDP. This wasn’t unusual, with the UK having run a shortfall on its trade in every year since 1998. The UK is the world’s second

largest exporter of services, after the United States, and habitually generates substantial surplus. But this is hardly ever enough to make up for the big shortfalls on trade in goods. Although recent years have seen relatively lacklustre economic growth at home, with GDP expanding by less than 2% every year since 2016, the global economy has enjoyed a relatively robust streak after the wobble that emanated from China in the middle of the last decade. The competitiveness of British products and services has also been enhanced by sterling’s depreciation following the EU referendum in 2016. So, after a period of sluggish export growth in the years following the recession of 2008-09 (exports even fell slightly in 2014 and in 2015), the past few years have seen a marked change of gear. The result was that in 2019 the value of total exports was nearly a third higher than it had been four years earlier.

As ever with trade data, there are some caveats. Some of the growth in the past few years has been down to a doubling in the value of oil exports during 2017 and 2018, followed by a surge of outbound gold shipments in 2019. But even taking account of these, exports in 2019 were still 29% higher than in 2015. With imports growing at a similar pace – 31% between 2015 and 2019 – the trade balance has varied little and shown no clear direction.

A key development in 2019 was an apparent surge in sales to China, propelling it into third spot in the ranking of export markets for goods. Indeed, if the £25.1 billion of exports to Mainland China is combined with the £9.4 billion that went to Hong Kong SAR, then the total of £34.5 billion wasn’t far behind the £36.6 billion of goods that was shipped to second-place Germany. But before we get carried away with any notions that Britain has taken advantage of the trade spats between China and the United States, the fact is that almost all of last year’s increase in exports to Mainland China was the result of gold shipments, which were negligible in 2018 then surged to around £5 billion last year. London has always been a major centre for trading in precious metals,

but it’s only in the past year or two that the value of inbound and outbound shipments has exploded. It should be noted that this is “non-monetary gold”, and nothing to do with any movement of gold that forms part of the reserves held by the Bank of England and other central banks. In the overall ranking of export markets, taking account of services as well as goods, China remained in sixth place.

In due course, it’s likely that Brexit will lead to a shift in the geographic pattern of the UK’s exports and imports. EU countries will always be major trading partners, simply because they are similar economies and because they are geographically close. Yet last year saw a small decline in the value of exports to the EU, while the EU share of Britain’s total trade was, at 47.3% at its lowest for at least two decades. These shares are prone to bounce around somewhat, and in any case the EU has been waning in importance as a trading partner for the UK for at least a decade as global economic activity has tilted towards China and other emerging economies. It is likely, however, that the reconfiguration of supply chains ahead of Brexit has had an impact on the figures. This could be the result of EU-focused supply chains reducing their purchases from the UK, to avoid increased complexity, or of British firms seeking to mitigate this

continued to expand at a robust pace, with the value of bilateral flows in 2019 being more than two fifths higher than in 2015. As a result, the USA alone now accounts for almost a sixth of Britain’s trade.

Mainland China fell by over 60%. It was not until March (after children had enjoyed their half-term ski breaks) that the pandemic started to take a toll on trade in services, with the widespread cessation of travel and tourism activities being the principal culprit. As for imports of goods, it wasn’t until April, by which time the UK was in a full-blown lockdown, with all non-essential shops closed, that the flow of goods imports was choked off.

in gold shipments had already narrowed the gap in the second half of 2019, but over the first nine months of this year, exports have exceeded imports by a not inconsiderable £22 billion. This doesn’t mean that the balance of payments current account will be in surplus. Far from it. There’s still plenty of accounting to go through to get from the trade balance to the current account, and most of it has continued to be deeply negative.

The slump in imports of services was especially marked, with a decline in value of 45% between December and April. We Brits are notoriously fond of foreign holidays (which count as ‘imports’ of services), and with these off the agenda from early March onwards, the amount spent on travel and tourism slumped by nearly 90%, compared to the final quarter of 2019, to a paltry £1.5 billion in the second quarter of this year. Unlike goods, where most categories saw declines, service sector trade outside of travel and tourism was only lightly impacted, and the figures for both exports and imports show no obvious signs of a major economic shock.

For businesses exporting goods, the revival started in a small way in May. By that time, the economies of China, South Korea, and some others in Asia were back on their feet, while European economies were also beginning to unlock. Imports of goods didn’t begin to revive until June, which saw the re-opening of ‘non-essential’ shops and the resumption of activity at factories and construction sites. In June alone, the value of goods imported into the UK surged by a sixth, or by just over £5 billion. With another surge in September, goods imports were by then only 1% shy of their level in December of last year. With many consumers forced to save during the spring lockdown, demand in recent months has been brisk, with people shelling out on electronic gadgets, new furniture, including for gardens, and household appliances. In September and October, non-food retail spending was higher than it had been a year earlier. This partly explains why imports from China are likely to be higher in 2020 than they were last year. Although imports fell sharply from February, they’ve recovered strongly, so that in the period

from January to September they were nearly 4% ahead of 2019’s figures.

on machinery, cars, aircraft, chemicals, oil, and pharmaceuticals. The trade in crude and refined oil, for instance, is still running at roughly half its pre-Covid level, thanks to lower demand from drivers, who are using their cars less often, and lower prices. Meanwhile, despite a revival in recent months, exports of cars during the first nine months of this year were more than a third down from a year earlier. In other product areas, however, such as food, beverages, and chemicals, trade has continued to flow relatively normally.

Exports to China in the first nine months of 2020 were down by a fifth, compared to 2019, though the picture is muddied by oil, where sales plunged by around two thirds. Excluding oil, the value of exports rose by just over2%, thanks in part to stronger car sales. This is a reflection of the degree to which the recovery in China has

broadened out to include consumer spending, and in any case follows a poor patch for the automotive market in 2019. In other export markets, there is a clear divide between those countries which, like the UK, have been hard hit by the pandemic, and those which have been less affected. So, apart from non-oil shipments to China, exports were markedly higher to Norway (thanks to deliveries of oil production platforms); moderately higher to Hong Kong, South Korea, and Australia; and were only fractionally lower to Taiwan. Among the larger markets, however, shipments fell by around a quarter to France, and by a fifth to the United States.

For trade in services, the recovery has been sluggish, as well as erratic, reflecting the continuing restrictions on international travel, with many “corridors” being opened up only to be closed again as the second wave made its appearance. Although some people were still keen to take their dose of Mediterranean sun, this wasn’t enough

to move the dial, so that by September imports of services were still nearly two fifths lower than in December, while exports were down by a sixth.

Taking goods and services together, the situation, as of September, is that exports were still 20% lower than in December, while imports were 14% down. The UK continued to trade at a surplus, but only a small one, which will probably disappear when Brits are once again able to take their holidays abroad.

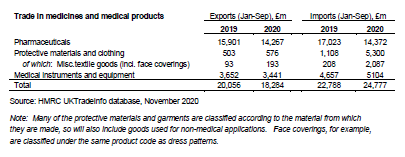

£12.5 billion, with prices being roughly five times higher than they were before the crisis. So it’s hardly surprising that recent months have seen a huge increase in imports of PPE into the UK, with inbound shipments of face coverings and masks amounting to over £2 billion in the first nine months of this year, ten times more than in the same months of 2019, of which 90% came from China. Meanwhile, trade in pharmaceutical products has been slightly lower than usual, perhaps reflecting an unfortunate consequence of the pandemic as people have deferred treatment for other medical conditions, and as elective surgery and scheduled treatments have been postponed to preserve hospital capacity. In the medical equipment category, imports have been boosted by a six-fold increase in purchases of breathing apparatus and a five-fold increase in protective goggles and spectacles.

Trade in PPE will remain at an elevated level for some months to come. Recent media reports have highlighted the delays at the port of Felixstowe, where an increase in traffic due to pre-Brexit stocking has been exacerbated by 11,000 containers of PPE being brought in to facilitate the roll-out of Covid vaccines from early next year. The development of vaccines and the need to distribute them globally will inevitably boost trade in pharmaceutical products, especially if it proves necessary to vaccinate against Covid annually.

on consumer spending, while manufacturing activity and construction sites have remained open. Trade flows in the closing months of 2019 will also be boosted by stockpiling ahead of the end of the EU transition period on 31 December, and as PPE is shipped in ahead of vaccine roll-out. Both these factors are, however, likely to fade as we go through 2021. And there will be new frictions in trading with the EU: apart from the additional costs that will be incurred in shipping goods, trade in financial services will also be negatively impacted by the loss of ‘passporting’ rights between the UK and the EU, while tourism and travel will not return to normal until at least mid-year. It’s therefore anticipated that the flow of trade in both directions will be lower in 2021 than

it was in 2019, although the negative impact on exports might be softened if sterling depreciates further.

Head of Economics, Commercial Banking

HSBC UK

Issued by HSBC UK Bank plc